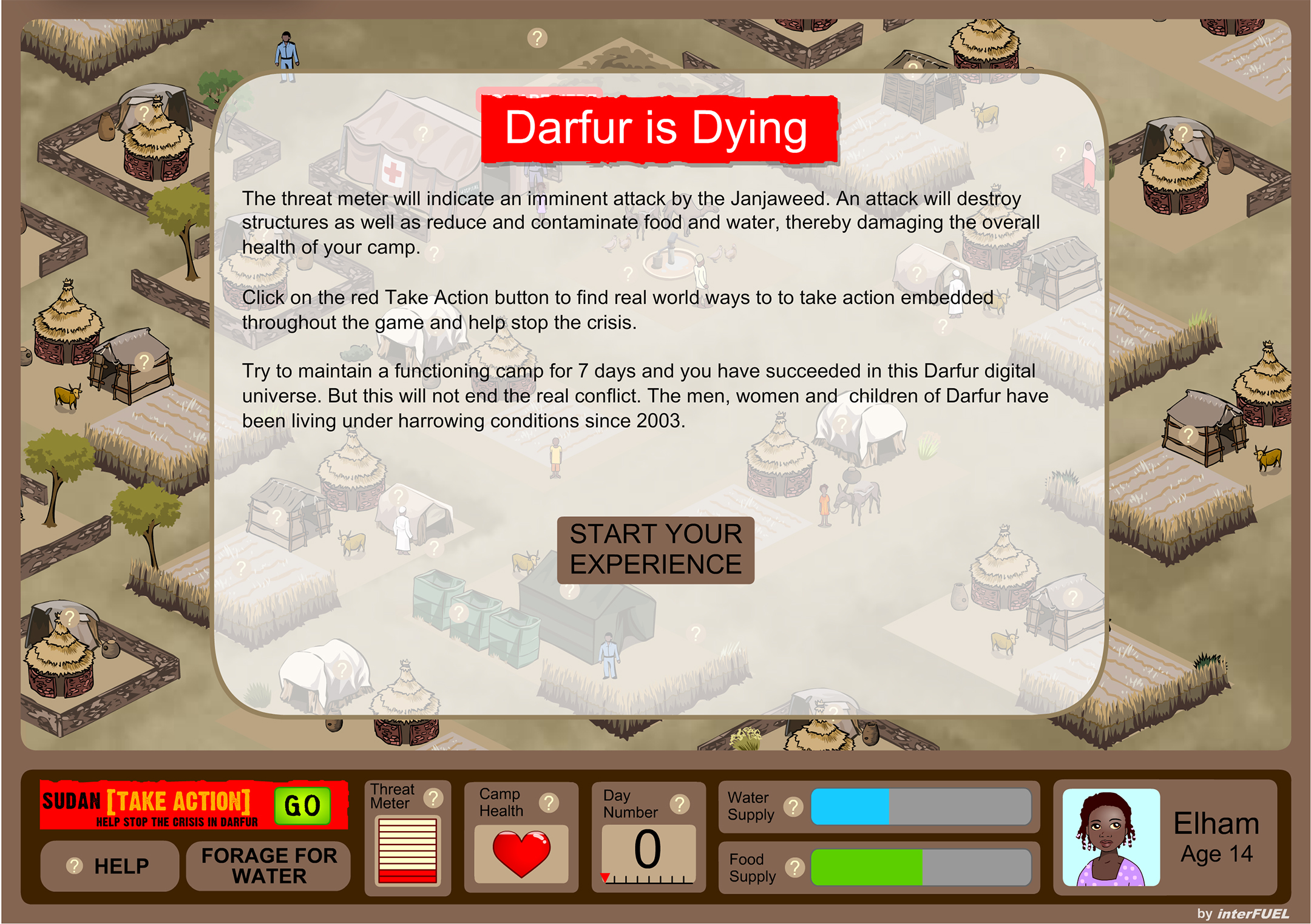

Darfur is Dying

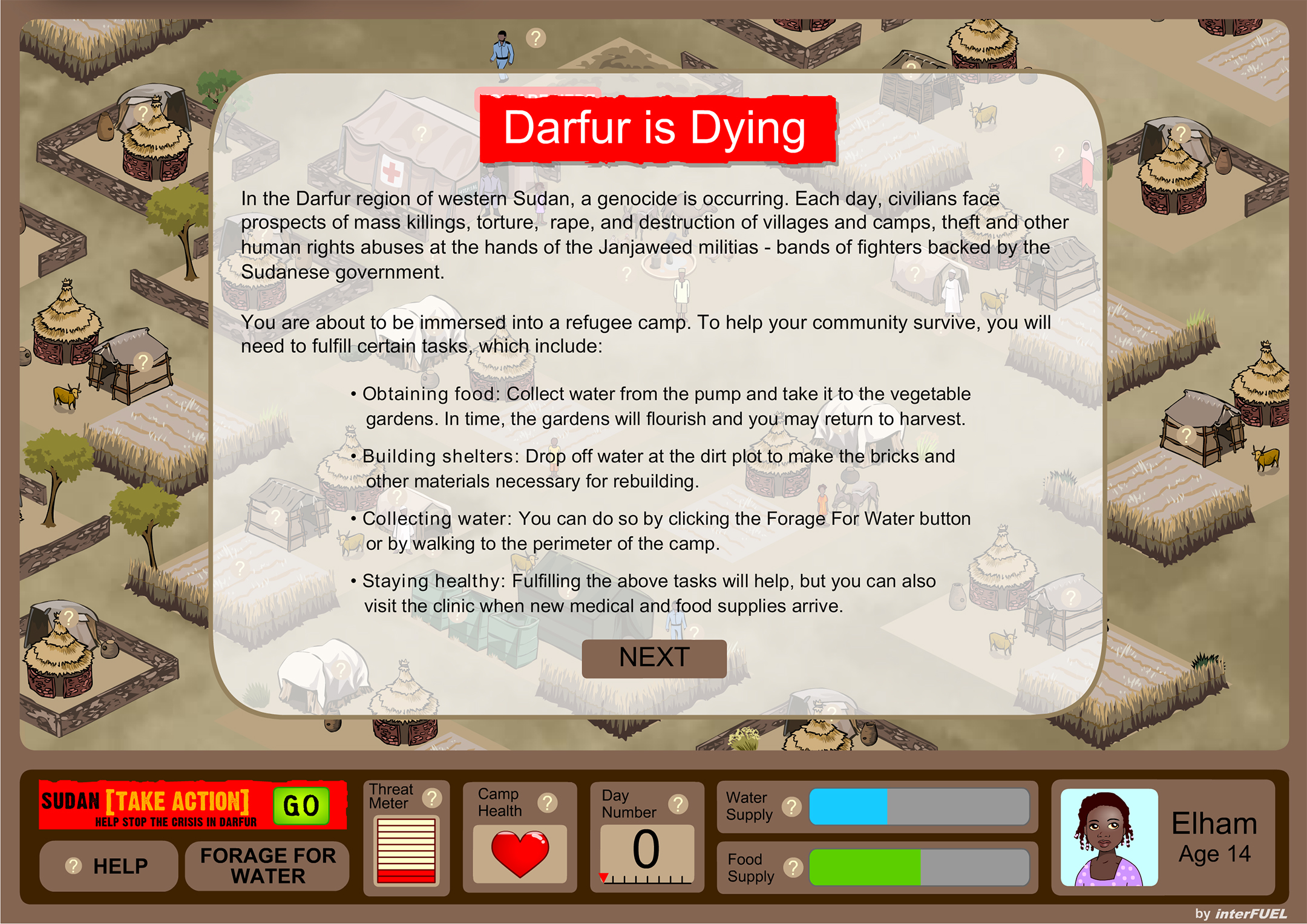

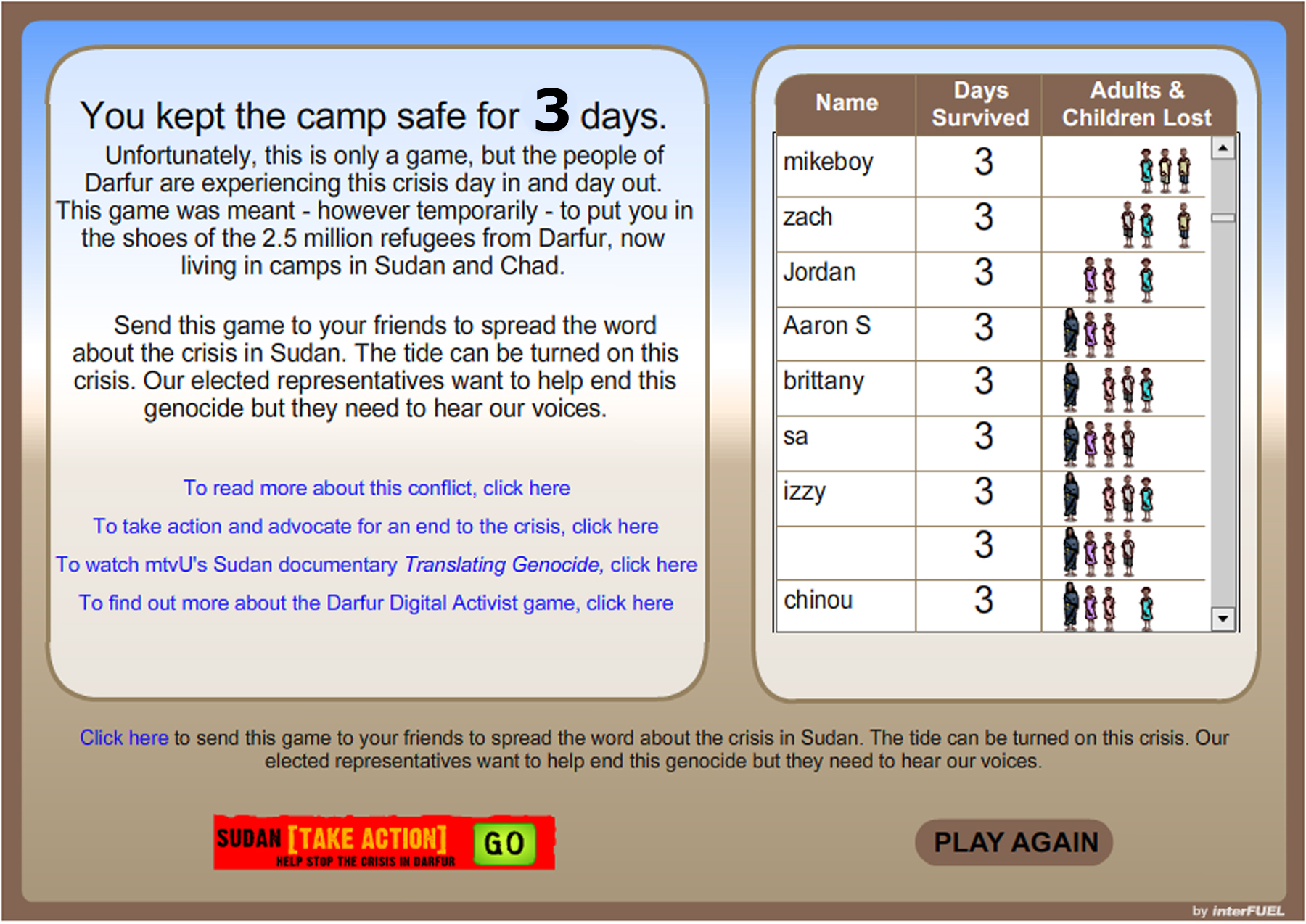

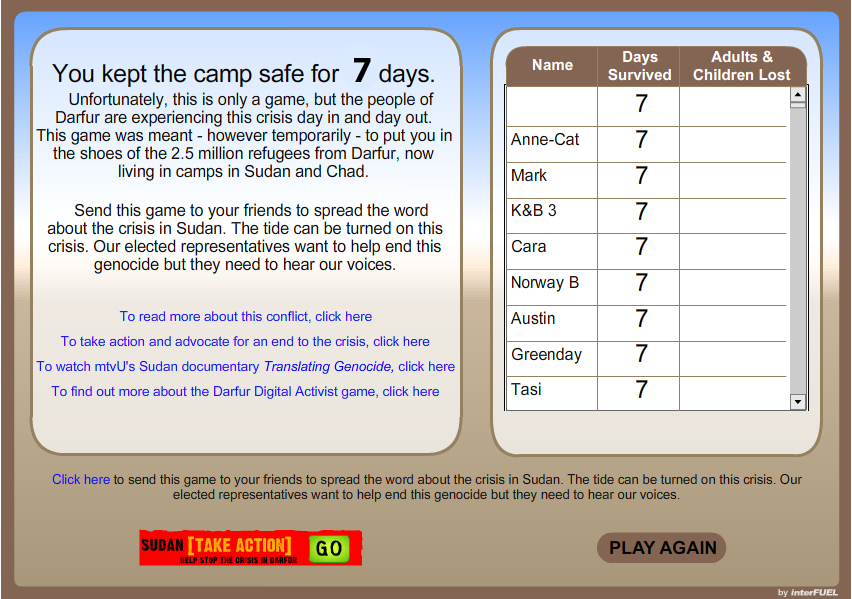

“The game serves as an informational entryway to the humanitarian crisis in the Darfur region of the Sudan and weaves uncomplicated and immediate mechanisms into the gameplay that seek to effect real world change. More than 700,000 people played the game in the first month after its release and that number grew to well over three million players.”

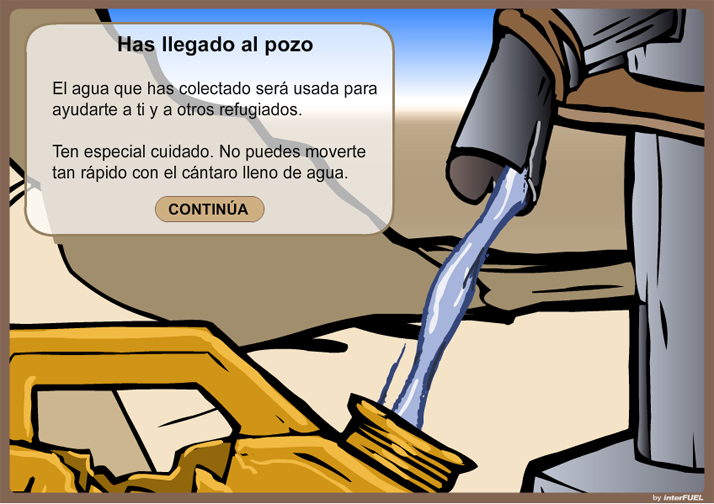

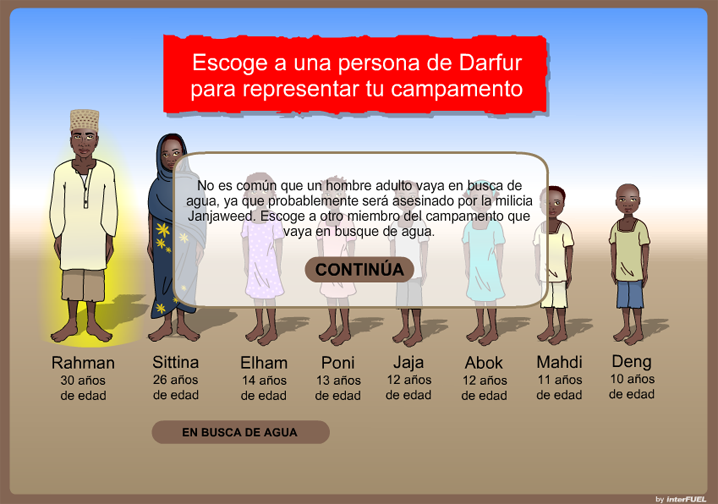

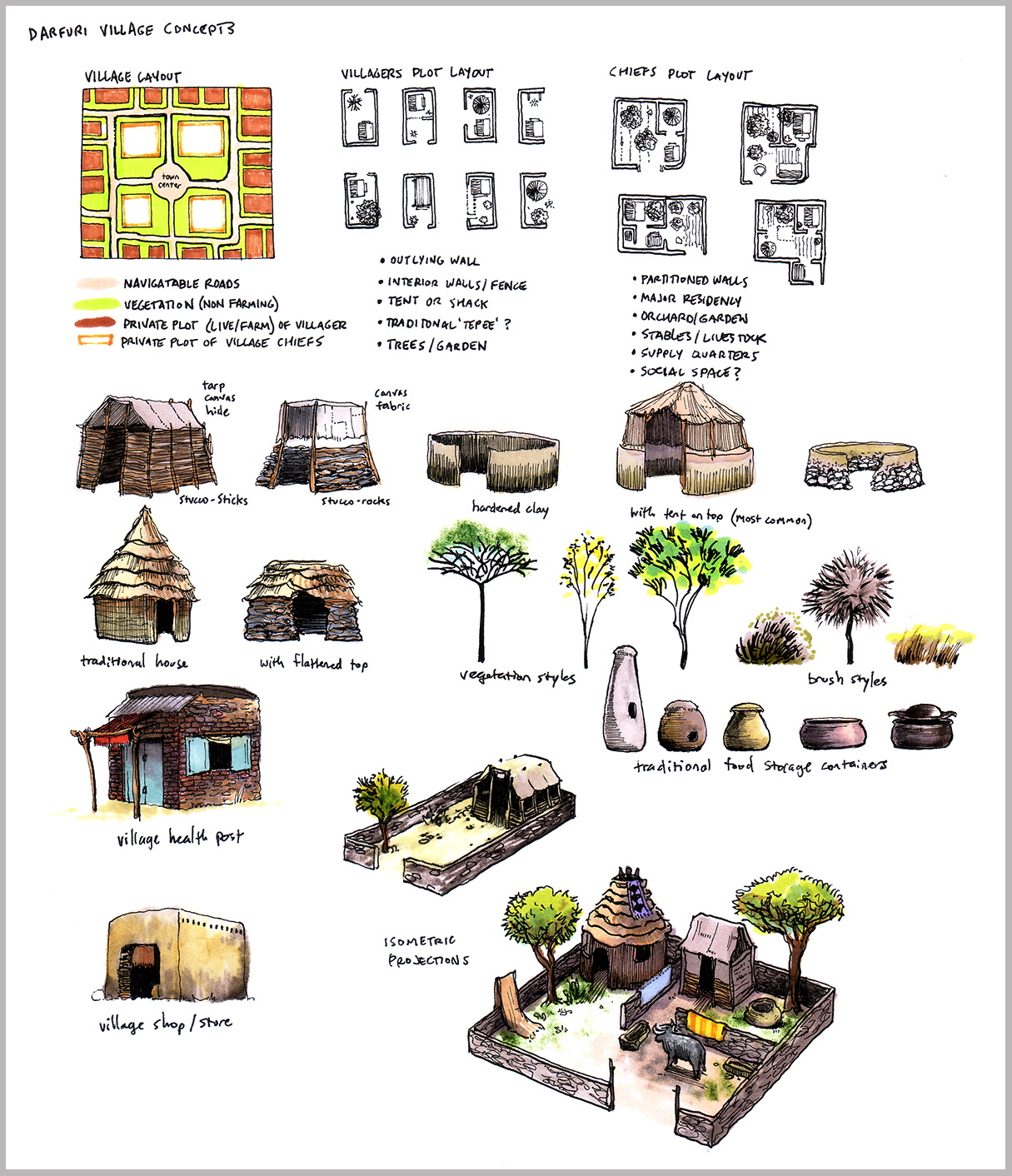

“The campaign brought together student tech-based activism. We worked closely with humanitarian aid workers who had extensive on-the-ground experience in Darfur. Gameplay focused on the difficulty of keeping a displaced persons camp functioning in the face of violence by militias. The game was translated to Spanish, Chinese, and Arabic.”

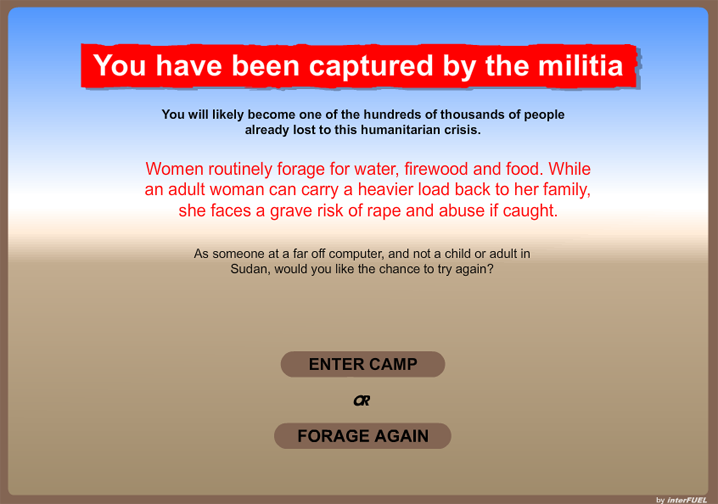

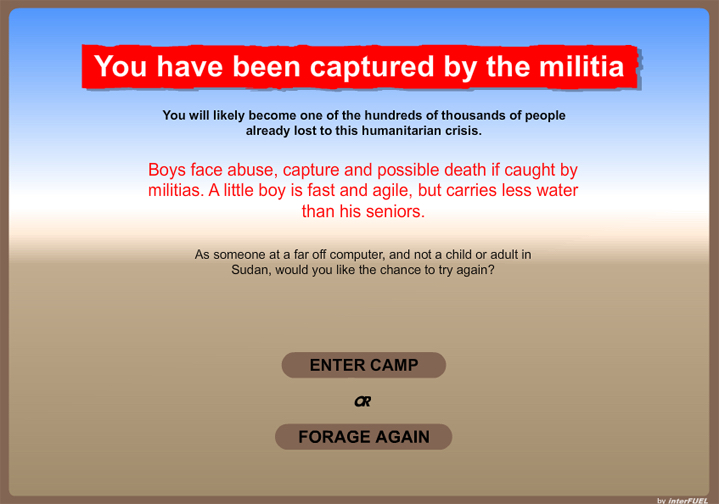

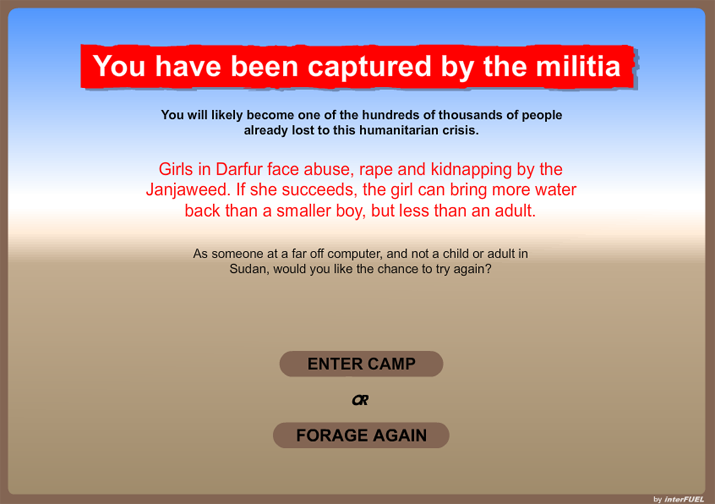

Darfur is Dying constructs an experience in which the player could become emotionally invested via factual personal narratives and testimonials. It then pulls back and offers a broader context of the extremely complicated issue. Finally, the design team wanted to ensure that the player had an immediate and simple means to make a difference in the real world in some small way, especially given the U.S. government and mainstream media's stark silence on the crisis at the time.

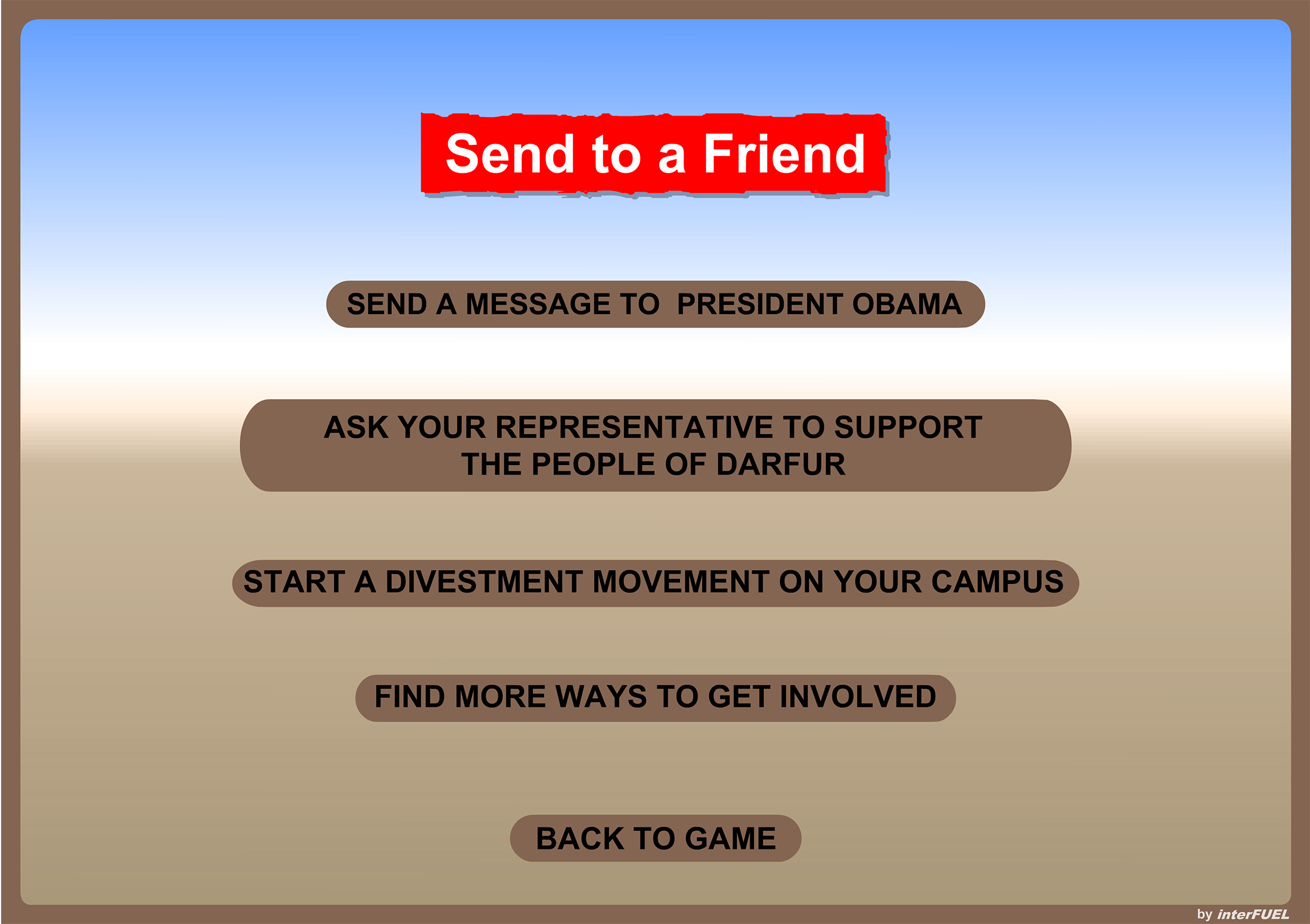

The game raises awareness about a current and ongoing genocide and mobilizes American college student communities. The design team strongly felt that playing through a portrayal of genocide would be entirely disheartening were it not for a chance to spread awareness about the crisis, learn about divestment on one’s college campus, sign a petition, or write a letter with the goal of persuading decision-makers to respond. “Direct action tools” woven into the game’s reward structure prompted players to take actions that had an effect in the real world. For example, the player’s chances of virtual survival improved if she petitioned her real-world U.S. Congressional representatives to enact legislation that aids the people of Darfur, if she shared the game with her social network, etc.

The game launched in 2006, before the cultural proliferation of casual games playable on social networking platforms like Facebook and before the trends of “gamification.” The game’s mechanics incentivized players to conceptualize the virtual and the real world as coextensive rather than unconnected. The team did not conceive of game space as fictionalized by definition nor did we understand lived experience as impervious to play. Rather, we imagined that it is when a game requires that the player reflect upon her own place in the real world and its systems, as well as upon her behavior, assumptions, and societal norms, that the “power gap” between those who experience oppression and those who hold greater social privileges can directly be addressed through gameplay. In an independent study conducted by researchers from Michigan State University, it was demonstrated that playing Darfur is Dying “elicited greater role-taking and resulted in greater willingness to help the Darfurian people than reading a text conveying the same information” (W. Peng, M. Lee and C. Heeter).

Awards and Press

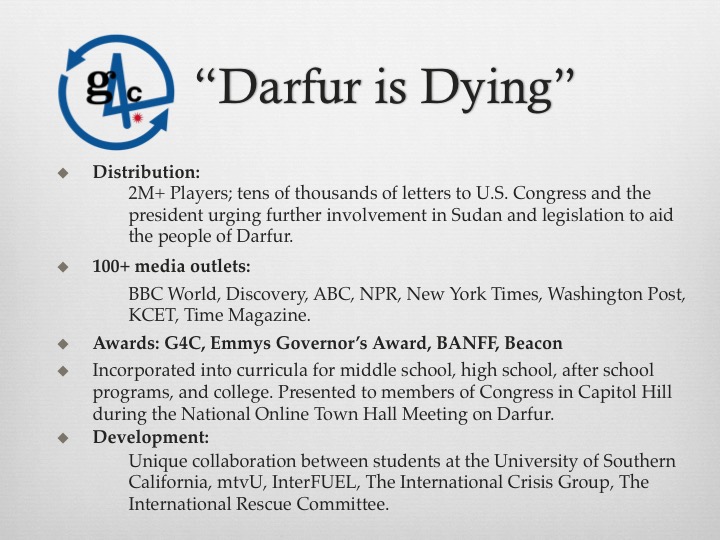

Darfur is Dying helped garner the prestigious Governor's Award (the Emmy's highest honor) at the 2006 Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Emmys as a core component of the MTV transmedia campaign in Sudan. It won the Games For Change 2007 Audience Award, the 2007 Beacon Award from the Cable Television Public Affairs Association in the New Media Category, the 2007 Canadian BANFF World Television Award for Best Internet Only Production, the 2007 Gold Davey Award for Activism, and was a 2007 Webby Award Activism Honoree. The project was presented to members of the U.S. Congress in the United States Capitol during the National Online Town Hall Meeting on Darfur. It has received acclaim from subject matter experts and academics, and was said to be "one of the best representations of life in Darfur" by New York Times journalist Nicholas Kristof, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on Darfur. It has been formally and informally incorporated into numerous K-12, after school, and college curricula.

Anti-oppressive Game Design

The game was part of an unprecedented competition in partnership with mtvU - the college arm of MTV Networks - for the Sudan Darfur Digital Activist campaign. The partnership included the Reebok Human Rights Foundation, the International Crisis Group, The International Rescue Committee, interFUEL, and the University of Southern California. The team consulted with the The International Crisis Group and various other individuals and groups, including those with expertise on the genocide and those who spent time in the region. We consulted with activists, scholars, filmmakers, and a former U.S. Marine and U.S. representative to the African Union. However, we did not get the opportunity to speak with Sudanese experts who may have witnessed what was happening and who were much closer to the politics and history of the region. It was an element that did not match with our goal of ethical design, as more people from outside of the situation were contributing to the project than those internal to it. While our methods are constantly evolving as we grow (as creative professionals and as human beings), you may read more about our philosophy and methodology here.